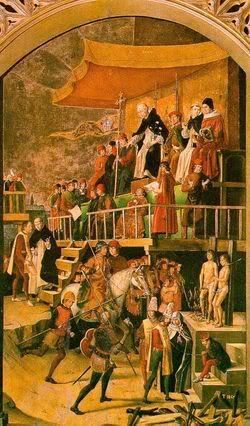

The words 'heresy' and 'heretic' may conjure up a sinister image for many, harking back to medieval times when there was much ado about such things. People willing to inflict injury, torture, and death, other folks willing to endure the same, all for the sake of some theological details. We tend to look disparagingly, or at least condescendingly, upon the primitive narrow-mindedness that would not esteem diversity of thought as we do today. Enlightened and educated, we now regard differences of opinion on such matters as a healthy thing, certainly not a cause for extreme reactions.

The words 'heresy' and 'heretic' may conjure up a sinister image for many, harking back to medieval times when there was much ado about such things. People willing to inflict injury, torture, and death, other folks willing to endure the same, all for the sake of some theological details. We tend to look disparagingly, or at least condescendingly, upon the primitive narrow-mindedness that would not esteem diversity of thought as we do today. Enlightened and educated, we now regard differences of opinion on such matters as a healthy thing, certainly not a cause for extreme reactions.

With that in mind, i recently looked into the etymology of the word 'heresy', and found that it was originally a quite innocuous term, even mundane. It comes directly from the Greek word αιρεσις (airesis or hairesis), which just means 'choice' or to 'choose' or 'select'. It's what the Greeks did at their market, and what you do at the mall or supermarket or video store. You pick and choose. You don't like that brand of peanut butter; you prefer this brand. That movie looks boring, but here's one that might be interesting. Certainly nothing evil or threatening in that. Choice is a good thing.

Well, i suppose it might be allowed that in some areas, a completely open-ended choosing might become problematic. We generally recognize, for instance, that in the military there needs to be a chain of command; it wouldn't work to have each individual soldier freely choosing what action to take. Likewise, in business, individual employees must sacrifice some autonomy and work to advance the collective success of the company, else the business will likely fail. Generally speaking, any human enterprise involving teamwork will necessarily also involve some curtailing of individual choice. Unity in religious faith is a special example of this. The bond of cohesiveness between believers assumes substantial agreement as to what beliefs they hold in common, else there is no bond.

But unity of faith goes beyond the teamwork priciple. The very pursuit of eternal truth presupposes that the truth is, in fact, attainable, and that other beliefs are therefore false and misleading. If truth exists at all, it must exist universally, and it must be singular. Pluralistic truth is an oxymoron. To speak of my truth is to speak of something that cannot be applied to others; i may as well speak of nothing at all. By contrast, the truth is worth speaking about, perhaps even arguing over.

The notion of pluralistic or relative truth carries with it the idea of the sovereignty of each individual self to decide what is and isn't true. So, besides being oxymoronic and intellectually untenable, this approach is essentially self-centered and arrogant, in that it vaunts the individual person's opinions above other considerations. Such intellectual myopia and self-centeredness would not seem to indicate a healthy faith. The more humble and honest approach would be to forget about pursuing my truth, and simply receive the truth as revealed and taught. Two examples:

The typical Evangelical proclaims the Bible to be the authoritative teacher of religious truth. But if that believer begins to 'pick and choose' which Scripture texts he will swear by, while ignoring, discounting, or explaining away the passages he doesn't like, that believer has ceased to be a true disciple and student of the Word, and has assumed the role of its critic and master instead.

In the same way, by claiming to be a Catholic, the Catholic believer implicitly accepts the Church as the authoritative teacher on matters of faith and morals. But if he freely selects which doctrines he will or will not hold, he is no longer a real Catholic. That is, his privately maintained beliefs cannot credibly be called 'catholic' or 'universal'.

So, to exercise airesis, to pick and choose what to believe, is incompatible with genuine faith. This is what the word heresy means.

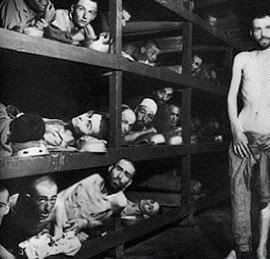

And when you really think about it, these issues may be pretty important after all. Ideas do have consequences.

What you believe will inevitably impact how you live your life, and will ultimately make our world either better or worse, depending upon whether your core values were good to start with. Those dusty theological details end up having enormous consequences.

What you believe will inevitably impact how you live your life, and will ultimately make our world either better or worse, depending upon whether your core values were good to start with. Those dusty theological details end up having enormous consequences.

Consider this: The Holocaust didn't just happen spontaneously. Early last century, a certain Margaret Sanger (founder of Planned Parenthood), and others, began to develop ideas about a master human race, the elimination of 'human weeds' (inferior races), and the deliberate undermining of Church authority to bring this about. Many leaders in the Third Reich acknowledged the writings of Sanger as the philosophical platform upon which they built their programs. If a strong resistance to heresy had been in place at that time, these racist and genocidal ideas would likely have remained the private thoughts of a few miserable souls, and would never have been admitted into matters of German policy.

This brings us back to the original questions. Is a concern over truth vs. heresy a dangerous attitude? Or merely rigid and antiquated? Or is heresy itself more dangerous and potentially fatal? Might those medieval folks actually have something to teach us today? Is 'agreeing to disagree' an enlightened attitude? Or a deadly one? Or, perhaps, merely a lazy and apathetic one?

No comments:

Post a Comment